Did you know the 2018 Video Showcase had over 70,000 unique visitors from 180 countries? Register to become a presenter today! http://ow.ly/51J030nkTCD http://ow.ly/i/KCMay

A video by @CADREK12 discussing the impo

A video by @CADREK12 discussing the importance of broadening participation in #STEM education. TERC is proud to have been able to provide some footage for this great video. #NationalSTEAMDay

TERC at AGU

Ken Mayer for TERCtalks

The American Geophysical Union is meeting this week in San Francisco (December 9-13) and climate change is one of the major topics of conversation. TERC had a critical role in organizing the climate literacy and education sessions occurring this week, and for the first time ever there will be Union Session (a particular kind of session at the annual meeting) focused on climate literacy education and engagement. If you are not at the conference, there are virtual options available.

I should also mention that TERC’s own Tamara Ledley will be honored at the meeting with an AGU Excellence in Education Award.

Climate Literacy Sessions at AGU Fall Meeting – December 9-13

Monday Oral Sessions

8:00-10:00 & 10:20-12:20: Climate Literacy and the Next Generation Science Standards for K-12 Education I and II– 103 Moscone South

8:00-10:00 & 10:20-12:20 Climate Literacy: Beyond Climate Literacy – Toward Effective Responses to Global Change I and II – 104 Moscone South

1:40-3:40 & 4:00-6:00 Climate Literacy: Achieving Widespread Climate Literacy Through Innovative Engagement Strategies, Effective Partnerships, and Large-Scale Networks I and II – 103 Moscone South

Monday Posters

1:40-6:00 Climate Literacy: Beyond Climate Literacy – Toward Effective Responses to Global Change III Posters – Hall A-C Moscone South

Tuesday Oral Sessions

8:00-10:00 Climate Literacy: Achieving Widespread Climate Literacy Through Innovative Engagement Strategies, Effective Partnerships, and Large-Scale Networks III – 103 Moscone South

4:00-6:00 UNION SESSION: Climate Literacy: The Role of the AGU Scientific Community in Climate Change Communication and Engagement – 102 Moscone South

Tuesday Posters

1:40-6:00 Climate Literacy: Achieving Widespread Climate Literacy Through Innovative Engagement Strategies, Effective Partnerships, and Large-Scale Networks IV Posters – Hall A-C Moscone South

1:40-6:00 Climate Literacy and the Next Generation Science Standards for K-12 Education III Posters – Hall A-C Moscone South

Wednesday Oral Sessions

8:00-10:00 Climate Literacy: Barriers, Misconceptions, and Progress in Improving Climate Literacy I – 103 Moscone South

8:00-10:00 Climate Literacy: Beyond the Comfort Zone – New Approaches to Climate Change in Higher Education I – 104 Moscone South

10:20-12:20 Climate Literacy: Impacts, Evidence, and Best Practices from Research and Evaluation I – 104 Moscone South

Wednesday Poster

1:40-6:00 Climate Literacy: Barriers, Misconceptions, and Porgress in Improving Climate Literacy II Posters – Hall A-C Moscone South

1:40-6:00 Climate Literacy: Beyond the Comfort Zone – New Approaches to Climate Change in Higher Education II Posters – Hall A-C Moscone South

1:40-6:00 Climate Literacy: Impacts, Evidence, and Best Practices from Research and Evaluation II Posters – Hall A-C Moscone South

Thursday – Workshop

8:30-5:00 Preparing for Global Change: Education, Collaboration and Community Engagement to Enable a Science Savvy Society Workshop – San Francisco Marriott Marquis-Golden Gate A

Investigating Science Outdoors with an iPad?

Ken Mayer for TERCtalks

Grab your iPad and head outdoors to start exploring the world around you. That’s the idea behind TERC’s new eBook, Investigating Science Outdoors, which is now available to teachers, after school providers, and home schoolers for free from Apple’s iBook store! The supplementary science curriculum gets students (ages 12-16) outdoors, exploring the world around them, learning science observation and investigation skills, and actually doing science.

I’ve downloaded the book already and am ready to start selecting a study site with my kids. I am motivated by my own curiosity and a bit of parental angst. Thanks to my recent read of Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv, I worry that I could be raising children with nature-deficit disorder. I am hoping that Investigating Science Outdoors will strengthen how my kids connect with nature as well as lessen some of my parental anxiety. I do have one concern though — given that I sometimes struggle to get my kids to abandon their 2D screens for the 3D world — will bringing the iPad outdoors really help them explore, or will they just stayed glued to the screen?

I’ve downloaded the book already and am ready to start selecting a study site with my kids. I am motivated by my own curiosity and a bit of parental angst. Thanks to my recent read of Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv, I worry that I could be raising children with nature-deficit disorder. I am hoping that Investigating Science Outdoors will strengthen how my kids connect with nature as well as lessen some of my parental anxiety. I do have one concern though — given that I sometimes struggle to get my kids to abandon their 2D screens for the 3D world — will bringing the iPad outdoors really help them explore, or will they just stayed glued to the screen?

Fortunately, I could put that question to TERC staff, namely Teon Edwards, a science curriculum and game developer who adapted units from TERC’s Global Lab curriculum to create the free ebook, and Jamie Larsen, a science educator, technology and life-science geek, and advocate for using games and technology to encourage kids to open the door and explore.

First to Teon I asked, Why an ebook?

“Because it’s portable, easy to use, and well, a lot prettier than the original curriculum.” As I hold the iPad and swipe my finger across the screen flipping through the pages, I have to agree. I imagine it is much easier to carry these into the field than the old 8 ½ x 11 paper guides and to the point of it being prettier, I realize it is more than just visual appeal. As I scan the pages on observing and recording nature patterns at the outdoor study site, it is obvious to me how the full-color images showing examples of rosette, spiral, and helix growth patterns in plants will inspire and challenge students to look deeper to find these patterns in their study site.

Teon points to the fact that many of the tools you need for collecting data can be  right on the iPad. On their own or through TERC’s eBook portal, teachers and students can find recommended apps for sketching, note taking, logging location, identifying plants and animals, and capturing photos and video. She adds, “Think about the power of being able to take a photo of a plant, pairing it with the notes and sketches you’ve made, and then identifying it with a specialized app like LeafSnap or an online identification guide. Teachers also have a complete Teacher Guide version of the eBook available to them right there at the study site, which makes preparing and facilitating the outdoor sessions much easier.”

right on the iPad. On their own or through TERC’s eBook portal, teachers and students can find recommended apps for sketching, note taking, logging location, identifying plants and animals, and capturing photos and video. She adds, “Think about the power of being able to take a photo of a plant, pairing it with the notes and sketches you’ve made, and then identifying it with a specialized app like LeafSnap or an online identification guide. Teachers also have a complete Teacher Guide version of the eBook available to them right there at the study site, which makes preparing and facilitating the outdoor sessions much easier.”

To Jamie I asked, “Won’t the iPad loaded with the recommended apps just distract the kids?”

“There is that potential, but these are the tools many kids are encouraged to use by schools adopting technology. It can actually help focus their questions,” he countered. “We should take advantage of the tools and student’s interest and enthusiasm in using them to help them document their site. The tools make it easier to collect observations and data to analyze back in the classroom. In addition, the tools provide a pathway to share what they discover through sites that encourage nature observation and citizen science.”

My conversation with Teon and Jamie made me think that the iPad outside might just help my kids spend a little more time observing the world around them. In addition to opening their eyes to uncovering the relationships between the living and non-living things at their study site, they might just be more aware and inquisitive the next time they go outside walking and playing without the screen in hand.

What do you think?

Investigating Science Outdoors is available from the iBooks store, we hope you get a chance to try it out, and if you do, or have questions, we would like to hear from you.

Ch-ch-ch-changes…

Kacy Karlen for TERCtalks

Arriving at one goal is the starting point of another.

—John Dewey, Democracy and Education

The first TERCTalks post went live on the otherwise mundane date of March 7, 2012. Thirty-five posts later, I am handing off the Bunsen to TERC staff. I’m confident that this blog will thrive with many different voices; not just one.

In a year’s time, TERCTalks became my labor of love as a writer—my opportunity to learn about and share insights great and small—gleaned from unpacking the compelling research endeavors of our staff. I got to sit down and chat with researchers deeply invested in making our world a better place through their innovative work across adult numeracy, educational gaming, early algebra, climate science, assistive technologies, data use, and electronic community development. I got to travel to classrooms, conferences, and pilot test sites and observe how TERC work is impacting the daily lives of teachers and students nationwide. I got to bask in that infectious love of learning, that passion for making education accessible and equitable that every TERC staff member embodies.

It’s a year later, and high time for this one writer’s labor of love to become a collective vision. Thank you for joining in the start of the conversation with me—I hope you’ll also join me in following its evolution!

Pt. II: Using Data Goes International with New Pilot from Kuwait’s Ministry of Education & MESPA

Kacy Karlen for TERCtalks

In continuation from Part I of “Using Data Goes International with New Pilot from Kuwait’s Ministry of Education & MESPA“, TERC’s Diana Nunnaley shared her experiences after her first trip to Kuwait as a data PD provider for the Kuwaiti Ministry of Education’s Improvement of Educational Management and Professional Development (IEMPD) project. Under the direction of the Massachusetts Elementary School Principals’ Association (MESPA), Diana and the Using Data team are ushering in this new school management and leadership pilot in Kuwaiti public schools. She chatted with me about the first phase of data work, her perspectives on education reform, and the value of data-driven decision-making across oceans and continents.

TT: So were these Kuwaiti educators and administrators already using data in their schools?

DN: In the majority of schools, using school, district, and national data to improve student learning was a brand new concept. Even when we talked about what kinds of classroom assessments teachers were using, it had been—for the most part—a very linear process. Teachers gave a test; it was graded; it went into the grade book. They got national results, and principals and districts looked at those—a process which led administrators to the conclusion that they needed to reform the whole Kuwaiti education system. But in the schools and at the teacher level—it was altogether rare that teachers had unpacked those national results at all.

TT: Can you tell me a bit more about Kuwait’s public education system? Is it similar to the public education system in the United States, or are there some significant differences?

DN: Like most places, there is a broad range of educator and administrator knowledge and experience. I met some administrators and educators that were very knowledgeable and doing things based on research, similar to educators here. What I noted as the main challenge for educators and administrators was conveying the Kuwaiti national curriculum. It offers up extensive content and syllabus depth, but only allows for the ‘memorize and regurgitate’ model in schools. Kuwaiti educators and administrators want to move toward ways to engage students in more authentic learning.

The sense I get from the educators and administrators is that historically, the Kuwaiti public school system has been very top-down. Directives came from the Ministry of Education, and went through the district with very explicit instructions to teachers as to how to carry out learning standards. But there has been a cultural shift with their reform movement, and now the Ministry of Education is looking to principals to become instructional leaders in their schools, and work collaboratively with faculty to shape what teaching should look like, accompanied by new standards. With this new plan, faculty are being given more trust and more agency in the classroom.

TT: You mentioned national testing, but are there any nationwide standards movements like the Common Core, or the NGSS? What is the reaction/feeling around implementing national standards?

DN: That’s exactly where Kuwait is going. The Ministry of Education’s international team of experts coming from the Curriculum, Research and Quality Assurance education departments of Romania, Estonia, and Uzbekistan is rewriting the curriculum. The new content areas are Arabic, English, mathematics and sciences. Their vision is to educate internationally-competitive students, supported by an engaged and efficient leadership and including a sustainable, long-term assessment system.

TT: What are your thoughts on the currency and relevance of data-driven PD programming and decision-making internationally?

DN: Data is a tremendous catalyst for helping people to examine long-held assumptions and raise important questions around learning goals, shared understanding of teaching practices, and student outcomes. What we’ve seen as Using Data facilitators is when you start examining learning objectives by getting educators to analyze student and classroom data collaboratively, teachers have those ‘aha’ moments around what standards really look like in practice and what the best pedagogical strategies for impacting learning are.

Importantly, delving into data helps pave the way to vertical articulation conversations —where you have, say, 7th grade teachers noticing student issues around ratio and proportion from their data, and beginning a conversation amongst themselves that leads them to conclude that students are getting hung up on fractions. From there, they have the fodder to chat with their early elementary teachers about what is being introduced around fractions in terms of language, manipulatives, et cetera. So then you have your primary teachers entering the conversation—the result is that you get a more coherent version of what learning is like, K-12, and how elementary educators can help build formative understanding from grade-to-grade.

Using Data gets teachers away from being alone in their classrooms, trying to figure it all out on their own. Engagement with student and school (and even district and national) data promotes a significant change in school cultures—where there are more open lines of communication, better pedagogical decisions made, and better student outcomes.

TT: Thanks so much, Diana!

For more information on Using Data, please visit: usingdata.terc.edu and join in the data-driven conversation on Twitter @TERCUsingData.

Pt. I: Using Data Goes International with New Pilot from Kuwait’s Ministry of Education & MESPA

Kacy Karlen for TERCtalks

I joined Diana Nunnaley, Project Director for Using Data, on one of her first days back from a whirlwind trip to Kuwait. As part of Kuwait’s Ministry of Education’s Improvement of Educational Management and Professional Development (IEMPD) project, Diana and the Using Data team have been selected as one of four PD providers by the Massachusetts Elementary School Principals’ Association (MESPA) ushering in this new school management and leadership pilot in Kuwaiti public schools. Diana chatted with me about the first phase of data work, her perspectives on education reform, and the value of data-driven decision-making across oceans and continents.

TT: Hi Diana. Thanks for joining me. So tell me a bit about how you got involved with IEMPD pilot…

DN: It all started with the work we’ve been doing for the last 3 years with the Massachusetts Elementary School Principal’s Association (MESPA) in Marlborough under Executive Director Nadya Higgins. We’ve offered two different Using Data leadership seminars there, and have had subsequent opportunities to work with schools and districts across Massachusetts.

Nadya herself is very much personally invested in education reform supporting administrators. She has been working with the Middle East Initiative at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University to bring educators and administrators from Kuwait to the U.S. to study education reform—Massachusetts is seen as a leader internationally in education reform!

Through her work with the Middle East Initiative—and after working with the Ministry of Education in Kuwait to create and deliver Study Tours—Nadya was invited to submit a proposal in response to an RFP for this pilot. As she has experienced our work and our reputation in the field of data-driven professional development, Nadya wrote us into the proposal to provide PD around collaborative inquiry and the effective use of data—we are one of four consultants, and the only data PD provider contracted through MESPA.

TT: Tell me about your first time in Kuwait, and any surprising moments you had.

DN: I think my greatest surprise was that—despite having a vastly different culture—Kuwait educators and administrators share the same kinds of goals we have for education here in the United States. On the surface, the Kuwaiti culture looks and sounds very different from those of the U.S. cities and towns where we typically work. But once we began talking to the Ministry of Education staff, school administrators, section leaders, and support staff about teaching and learning, we were all speaking the same language. Their passion for helping their students reach international standards of learning mirrors what educators here are also working to achieve.

This is an extremely ambitious project —the Ministry of Education is planning to implement new leadership roles and responsibilities, new teaching standards, new learning standards and eventually—new assessments. And these huge systemic overhauls will be happening simultaneously! We’ve been working at it for years here in the U.S. The teachers and school staff who volunteered to participate in this pilot have an enormous undertaking before them. But their willingness to be the first to implement totally new paradigms for teachers and students alike is more than commendable—it’s like they are the first astronauts to go into space!

TT: Would you mind elaborating on the kind of programming you implemented?

DN: The visit to Kuwait kicked off the first phase of our work. It was the first time we met our Kuwaiti educators at the district and school levels. Some of them have already been part of developing the new leadership standards for principals as part of this initiative; some of them have been part of the team developing new teaching standards for teachers and new curriculum in 6 content areas. But we got to introduce them to the key aspects of a new vision for school leadership. Our part of this first session was to begin to help them understand what effective data use looks like in schools and to engage them in talking about their challenges and views around data use.

We introduced our group to research supporting key factors and conditions in place to introduce, initiate, and support deep engagement with school data. I gave the group an opportunity to use a scale to predict their current data use and share their ratings with their colleagues. From there, we got into questions about who has access to data—whether it’s a lot of educators or just a few; whether decisions are made broad-base on use of data from teachers, administrators and specialists across schools, or whether decisions are made top-down; whether professional development is an event that happens when someone else somewhere else decides on it, or whether pd is ongoing, formative, job-embedded, and growing from regular teacher engagement with data. And we discussed whether or not there are supports in place for professional learning communities for teachers to regularly meet, talk about data, and enact solutions around their data analyses.

TT: Did you use any other models of successful data use?

DN: We shared a video that shows a principal and her staff analyzing their data and sharing their results with students to help them see what using data can look like in the classroom. Our pilot group noted what they observed from the principals; teachers; and the students in the video. Actually, one of the big aspects of the UD process is getting students to engage with their own data—helping them to begin to track their progress, set their goals, and monitor their processes on the path to achieving mastery.

Ultimately, from this visit, I needed to gather as much information as possible about their local context – what their current practice looks like and of course, more about the expectations for participants in the pilot project from the Ministry’s perspective. […]

For more information about Using Data, please visit: http://usingdata.terc.edu.

And tune in next week for Part II of “Using Data Goes International with New Pilot from Kuwait’s Ministry of Education & MESPA”!

Post-ISTE Musings: Small Fish, Huge Pond, But Lots of Bites…

Kacy Karlen for TERCtalks

Our recent trip to sunny San Antonio to exhibit at the ISTE 2013 Annual Conference and Exposition was somewhat of a ‘wild card’ venture—and not in the least bit because the mercurial summer weather. We hadn’t exhibited at the conference in several years. We had very little sense as to whether the tech-hungry ISTE audience—teethed on the numerous big name hardware, software, publishing, and product exhibitors—would react favorably to our research endeavors, thought leadership, and prototypes, many of which are available for free or at very nominal costs (we are a not-for-profit org, after all). At the cavernous Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, it wasn’t so hard for our team of two to start feeling like the smallest fish in the biggest pond…

![A small fry culled from a big pond. By U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://terctalks.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/sacramento_splittail_small_fish.jpg?w=600)

A small fry culled from a big pond. By U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Here’s what was luring ‘em in:

EdGE games1: The EdGE team was demoing their addictive particle physics game, Impulse!, in tandem with their captivating laser light game, Quantum Spectre. Both games are in beta versions and currently being pilot tested among high school audiences for efficacy in developing students’ implicit understanding of Newtonian laws of motion and optics. We invited booth visitors to try the games on our laptops and iPad, but versions are also for the Kindle and Android. On Tuesday of the conference, Impulse! went live on Apple’s App Store (for free), and by Friday, was one of AppAdvice’s “Best Apps”.

Signing Math and Science2: Judy Vesel’s signing math and science apps for deaf and hard of hearing students were eye-catchers for booth visitors interested in assistive technologies, and for good reason—the portable dictionaries and pictionaries are uniquely interactive learning supports. The flagship Signing Science Dictionary (SSD) is an avatar-based dictionary of science terms and definitions in American Sign Language (ASL) or Signed English (SE) for deaf or hard-of-hearing students in grades 4-8. A full selection of K-12 Signing Math and Science dictionaries and pictionaries is available for tablets, iPods, and iPhones from www.signingapp.com.

TERC’s Online Communities & Digital Delivery Models: From the successful third year of the IGERT Online Video and Poster Competition3 facilitated for NSF’s flagship Integrative Graduate Engineering and Research Traineeship to the expansion of the CLEAN Network4 of climate science and literacy stakeholders and resources, TERC’s reputation as a thought leader in online community development and facilitation precedes us—it even did at ISTE. Visitors to the booth also picked our brains about new digital delivery models for curricula and professional development—with The Inquiry Project ‘s grades 3-5 physical science curriculum5 and Talk Science PD available entirely online; new online coursework being served up from Investigations Workshops; and even more digital deliverables on deck; we felt—if not entirely MOOC-conversant—in-line with the times.

So here’s to taking the plunge and heading downstream to ISTE 2013. It was well worth the visit, and we should be seeing you as we come up for air next year!

1 Quantum Spectre and Impulse are part of EdGE’s Leveling Up project, funded by the National Science Foundation (DRK-1119144).

2 The Signing Science Dictionary (SSD) is funded in part by grants from NEC Foundation of America, the National Science Foundation (HRD-0533057), and the Department of Education (H327A060026)). The Signing Science Pictionary (SSP) was funded in part by grants from the Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family Foundation, Disability Inclusion Initiative and the Department of Education (H327A080040). The Signing Math Dictionary (SMD is being funded in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (HRD-0833969). The Signing Math Pictionary (SMP) is being funded in part by a grant from the Department of Education (H327A100074). The Signing Earth Science Dictionary (SESD) is being funded in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (GEO-0913675).The Signing Life Science Dictionary (SLSD) and Signing Physical Science Dictionary (SPSD) are being funded in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (DRL-1019542).

3 The IGERT Resource Center and the NSF IGERT Online Video and Poster Competition are funded by the National Science Foundation (DGE-0834992).

4 CLEAN is funded by grants from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NA12OAR4310143, NA12OAR4310142), the National Science Foundation (DUE-0938051, DUE-0938020, DUE-0937941) and the Department of Energy.

5 The Inquiry Project and Talk Science are funded by the National Science Foundation (DRL-0918435A).

Citizen Science, Engagement & the Changing Fells: A Chat with Brian Drayton (Pt. I)

Kacy Karlen for TERCtalks

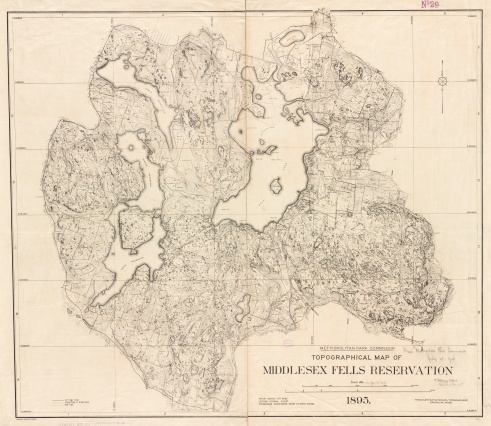

I had the opportunity to sit down for a chat with Brian Drayton, Plant ecologist, linguist, resident polymath, and Co-Director of the Center of School Reform at TERC. Brian is co-PI on an array of projects including MSPnet, A Research + Practice Collaboratory, The Atlantic Partnership for the Biological Sciences and Biocomplexity and the Habitable Planet, and just published “Under the Microscope”, a white paper review of the research literature on biology labs from 1987-2007. With expertise in topics spanning scientific inquiry, ecology and life science, electronic communities, and citizen science, Brian shared his thoughts in response to Carolyn Johnson’s recent special interest piece for The Boston Globe (in which he was quoted). We talked about the changing local landscape of the Middlesex Fells, Drayton’s field-altering Master’s thesis, “Plant species lost in an isolated conservation area in Metropolitan Boston from 1894 to 1993”; the role of citizen science; the vanishing boundary between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ science; and bringing back the joy to science engagement.

Swamp Candles/ Lysimachia terrestris, a plant found in the Middlesex Fells. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

TERCtalks: Thanks for joining me, Brian. So let’s jump right in. From your perspective, what’s the distinction between ‘amateur’ science and ‘professional’ science?

Brian Drayton: I think that someone has probably written a book about this, but if not, someone should. There’s a lot in that question. It’s a question that bears on TERC’s work in many projects, not even just in regard to citizen science. I am thinking of work like Kids Network, Star Schools, Global Lab, Teacher Enhancement in Ecology and Pedagogy, MSPnet, and many others in which scientists are somehow involved in science education. People have written about the inherent power or status thing—often non-scientists project onto scientists a certain elitism or sense of superiority that—in my experience—most scientists don’t actually feel, or actively try to avoid.

There’s that, and there is the fact that everyone has something that occupies their full attention and time, and that’s what they’re expert at. There are cultural aspects inherent here that make it possible for one to become a good teacher, or an involved citizen, or a scientist. For scientists—the fundamental thing is that you’re contributing to new knowledge by producing a coherent explanation about phenomena that appeals to data. As a scientist, you have to put out explications that anyone could observe by using your methods—so quality of data, reliability of measurement, and consistency of tools are crucial to your practice.

But I don’t like the tension between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’, because those are pretty arbitrary terms. Charles Darwin, Henry Cavendish, James Lovelock built labs, didn’t have appointments anywhere—semantically, they are ‘amateur’ scientists. The question really is: what standards are their scientific findings up to? Bryan Hamlin and his team are holding themselves to the standards that the scientific conversation requires, so the distinction is artificial—it doesn’t matter whether Hamlin is paid to do the work or not, or whether or not he holds a university appointment or not.

TT: Are there areas of field research that are inaccessible to citizen scientists? What are they?

BD: Objective data is the evidence you have to satisfy in science. And the tools and methods you use are shaped by the question you are trying to answer. If you want to have an accurate picture as possible of what plant species occur in the Middlesex Fells; where they are; how abundant they are—you can use remote imaging, but the best way to collect information is being there—observing the plant. Or preserving it. So you need good walking shoes and a hand lens, at least. It’s certainly possible to acquire the kind of knowledge and implements necessary to identify things, locate things, map things, whether stars or plants—in one’s spare time. There are people who have been cataloguing bird species in their backyards for 48 years. They are laboring in obscurity or largely unknown in the world of scientific journals, but have vast storehouses of scientific knowledge.

In fact, this kind of scientific knowledge and field research is absolutely indispensable, and we’re actually suffering right now because it is not being done more. It sounds crass, but a lot of science is done in the span of a PhD study. So especially in field research, when checking out change over time, or birds, or bats in an area—it’s fabulous if there are people providing reliable information about these topics who are familiar with a local area and continuously visiting it, year after year.

On the other hand, even when visiting the Fells—species like the oak can produce swarms of hybrids. Your research question may require you to know whether you are observing red or black oaks. In these cases, DNA techniques are really important for taxonomy as it’s rare that field marks are descriptive enough. Every year, species are being re-described on the basis of new molecular data. So there are certain hybrids you can’t define without high-tech tools, and the use of said tools require specialized science training—in mathematics, in methods, in instruments, in technologies. For certain cutting-edge applications of science—you have to travel the whole length of science that people took to get there.

TT: Thanks for clarifying. So can you describe your working relationship with Bryan Hamlin? You mentioned going out on walks with him?

BD: Bryan Hamlin contacted me in about the year 2000 or 2001, as he had been spending more and more time botanizing in the Fells. He started feeling like the data I had published just wasn’t extensive enough. He’s a very congenial guy and considerate—and he wanted to have a civilized conversation about the data, and that has been the relationship every since. When he and his colleagues started organizing this systematic study, they invited me to participate (I had moved to New Hampshire at that time and couldn’t work it in). But we stayed in touch, and caught up through the New England Botanical Club frequently—I shared my master’s thesis with him, and answered questions. We went out together trying to find plants, and had a very pleasant walk in the pouring rain. Even since the Globe story, we’ve exchanged a flurry of emails.

Topographical map of Middlesex Fells Reservation, 1895. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

TT: So it seems like a collaboration between a field botanist and a published scientist.

BD: I have enjoyed the whole process because it has recapitulated several ways that science works that I’ve experienced over the course of my career. I had to work full time in grad school. I was looking for an interesting study to do as a Master’s thesis around the topic of scientific apprenticeship. I was living in Medford at time and heard of a study done on the flora of the Fells in the 1890s. I thought that doing a retrospective to test some basic assumptions as to how conservation should be done would be interesting—and my advisor Richard Primack didn’t really know of any similar work that had been done—so I plunged in, and then published in 1993.

Once my paper was published, I became familiar with groups in Singapore and New York state asking similar questions around well-known local flora. So the first thing is that there was a convergence in that kind of study—it was in the air. My paper got picked up by the New York Times, and has been cited in other papers. Primack continued doing work with other students looking at climate change based on local, historical trends with his students. Years later, Hamlin and his colleagues starting noticing different trends and he set out to put together a greater systematic study of the Fells.

So in one way, my original study was superceded by a better study—but on the other hand, the proliferation of an idea is what I love about science. As a scientist, you hope for a little credit, you may hope that you get your name on the study you did, but mostly—you hope that other people use your study. And eventually, you hope that your study gets used enough, and recombined, and that the field advances and that your work is no longer relevant, as it’s superceded by more current research.

Stay tuned for Part II of “Citizen Science, Engagement & the Changing Fells: A Chat with Brian Drayton” !